CS295J/Research proposal

Project summary

Established guidelines for designing human computer interfaces are based on experience, intuition and introspection. Because there is no integrated theoretical foundation, many rule-sets have emerged despite the absence of comparative evaluations. We propose to develop a theoretical foundation for interface design, drawing on recent advances in cognitive science – the study of how people think, perceive and interact with the world. We will distill a broad range of principles and computational models of cognition that are relevant to interface design and use them to compare and unify existing guidelines. To validate our theoretical foundation, we will use our findings to develop a quantitative mechanism for assessing interface designs, identifying interface elements that are detrimental to user performance, and suggesting effective alternatives. Results from this system will be explored over a set of case studies, and the quantitative assessments output by this system will be compared to actual user performance.

A central focus of our work will be to broaden the range of cognitive theories that are used in HCI design. Few low-level theories of perception and action, such as Fitts's law, have garnered general acceptance in the HCI community due to their simple, quantitative nature, and wide-spread applicability. Our aim is to produce similar predictive models that apply to lower levels of perception as well as higher levels of cognition, including higher-level vision, learning, memory, attention, reasoning and task management.

We will focus on generating extensible, generalizable models of cognition that can be applied to a broad range of interface design challenges. Much research has accumulated regarding how people manage multiple tasks, and we will apply it to principles of how an interface should be designed such that it both helps maintain focus in a multi-tasking environment and minimizes the cost of switching to other tasks or applications in the same working sphere. The newer approach of distributed cognition also provides a useful perspective by examining the human-computer system as a unified cognitive entity.

Specific Contributions

- A model of human cognitive and perceptual abilities when using computers

- Impact: Such a model would allow us to predict human performance with interfaces. Validation of the model would allow us to more rapidly converge on ideal interfaces while simultaneously ruling out sub-optimal ones.

- 3-Week Feasibility Study: (1) Distill from review articles the major findings in all of the relevant subfields into a set of principles that will be grouped to form appropriate model components. Some of the most relevant subfields include: memory, attention, visual perception, psychoacoustics, task switching, categorization, event perception, and haptics. (2) Use these to devise a simple predictive model of human interaction. This model could simply consist of the set of design principles but should allow some form of quantitative scoring/evaluation of interfaces. (3) Develop a small set of 5-10 candidate GUIs that are designed to help the user accomplish the same overarching task(s) (e.g. importing, analyzing, and flexibly graphing data in Matlab). (4) Test/validate the model by comparing predicted performance to actual performance with the GUIs.

- Risks/Costs: There are always potential risks to any human subjects that might participate in testing the model which might necessitate IRB approval. Costs might include: (1) paying for any necessary hardware and software for developing, displaying, and testing the GUIs, and (2) paying for human subjects.

- A classification of standard design guidelines into overarching principles and measurement of the relation of each design principle with quantifiable cognitive principles (usability/cognition matrix). (OWNERS: E J Kalafarski, Adam Darlow)

- Components: 1) A ranking/weighting of the relevance of each cognitive principle to each design principle. 2) Specific rules for designing/assessing interfaces with respect to leveraging each cognitive principle for its most closely related design principles.

- Impact: With this proposal's stated goal of bringing together the independently-pursued but related realms of cognition and practical usability, such a classification plays a vital role in the concrete and extensible connectivity of other contributions of this proposal and their theoretical relationships and underpinnings.

- 3-Week Feasibility Study: 1) Parse from accepted and established design guidelines a number (5–10) of common concepts and rules in practical usability; 2) extract a comparable number (5–10) of cognitive principles from modern applications of cognitive theory; 3) construct a relational matrix of these concepts, establishing approximate weightings for the relationships between cognitive and usable principles and assigning unified UI suggestions to strongly-related pairs; 4) conduct a user study on a small number of highly-controlled UI variants (2–3) proving and refining several of the approximate weightings.

- Risks/Costs: Costs are low for a primarily-intellectual component, but the potential development of an encompassing framework and the vital role of providing a relational connection between the other disparate components of this proposal indicate a high payoff.

- A predictive, fully-integrated model of user workflow which encompasses low-level tasks, working spheres, communication chains, interruptions and multi-tasking. (OWNER: Andrew Bragdon)

- Traditionally, software design and usability testing is focused on low-level task performance. However, prior work (Gonzales, et al.) provides strong empirical evidence that users also work at a higher, working sphere level. Su, et al., develops a predictive model of task switching based on communication chains. Our model will specifically identify and predict key aspects of higher level information work behaviors, such as task switching. We will conduct initial exploratory studies to test specific instances of this high-level hypothesis. We will then use the refined model to identify specific predictions for the outcome of a formal, ecologically valid study involving a complex, non-trivial application.

- Impact: Current information work systems are almost always designed around the individual task, and because they do not take into account the larger workflow context, these systems arguably do not properly model the way users work. By establishing a predictive model for user workflow based on individual task items, larger goal-oriented working spheres, multi-tasking behavior, and communication chains, developers will be able to design computing systems that properly model users and thus significantly increase worker productivity in the United States and around the world.

- 3-week Feasibility Study: To ascertain the feasibility of this project we will conduct an initial pilot test to investigate the core idea: a predictive model of user workflow. We will spend 1 week studying the real workflow of several people through job shadowing. We will then create two systems designed to help a user accomplish some simple information work task. One system will be designed to take larger workflow into account (experimental group), while one will not (control group). In a synthetic environment, participants will perform a controlled series of tasks while receiving interruptions at controlled times. If the two groups perform roughly the same, then we will need to reassess this avenue of research. However, if the two groups perform differrently then our pilot test will have lent support to our approach and core hypothesis.

- Risks/Costs: Risk will play an important factor in this research, and thus a core goal of our research agenda will be to manage this risk. The most effective way to do this will be to compartmentalize the risk by conducting empirical investigations - which will form the basis for the model - into the separate areas: low-level tasks, working spheres, communication chains, interruptions and multi-tasking in parallel. While one experiment may become bogged down in details, the others will be able to advance sufficiently to contribute to a strong core model, even if one or two facets encounter setbacks during the course of the research agenda. The primary cost drivers will be the preliminary empirical evaluations, the final system implementation, and the final experiments which will be designed to support the original hypothesis. The cost will span student support, both Ph.D. and Master's students, as well as full-time research staff. Projected cost: $1.5 million over three years.

- A low-overhead mechanism for capturing event-based interactions between a user and a computer, including web-cam based eye tracking. (should we buy or find out about borrowing use of pupil tracker?) Should we include other methods of interaction here? Audio recognition seems to be the lowest cost. It would seem that a system that took into account head-tracking, audio, and fingertip or some other high-DOF input would provide a very strong foundation for a multi-modal HCI system. It may be more interesting to create a software toolkit that allows for synchronized usage of those inputs than a low-cost hardware setup for pupil-tracking. I agree pupil-tracking is useful, but developing something in-house may not be the strongest contribution we can make with our time. (Trevor)

- Accuracy study of eye tracking (2 cameras? double as an input device?)

- ???

- An extension to the CPM-GOMS model which accounts for dual-system theories of reasoning and cognition (OWNER - Gideon)

- Dual-process theories (Evans-2003-ITM) usually agree on the nature of high-level cognitive operations which are used in human reasoning. It is also argued that low-level processing, which is based on perceptual similarity, contiguity, and association, is determined by a set of autonomous subsystems. Depending on which system we use when performing cognitive operations, results can vary drastically. Our research project will contribute a set of guidelines to enhance classificatory decisions when implementing the CPM-GOMS model, resulting in more accurate predictions.

- Impact: The impact of this contribution will be an improvement on a well-established model.

- 3-Week Feasibility Study: In the course of 30 hours, we may perform a hand-analysis of the empirical results in cognitive psychology in order to develop a set of approximately 10 guidelines or rules.

- There is no risk for this contribution. Costs associated will be an extensive search of cognitive psychology literature for the past 25 years or so. Research on memory, reasoning, perception and more will be required in order to conduct a complete and accurate assessment.

- A method for collecting data on user performance in cognitive, perceptual, and motor-control tasks that requires less monetary cost, allows for a greater number of samples, and measures user improvements over time. (Owner - Eric)

- In order to reach a model of human cognitive and perceptual abilities when using computers, experimental analysis of human performance on these tasks will likely be necessary. User studies can often aid in this analysis, but they require much money, much time, and are subject to user fatigue. Alternately, we propose a web-based method for evaluating user performance in perceptual, motor-control, and cognitive tasks. The idea is to take a task would normally be measured through user studies in a laboratory and map this task into a simple online game. Somewhat similar work has been done by Popovic et. al. at the University of Washington, in that they took the task of folding proteins and mapped it into an online game ( http://www.economist.com/displaystory.cfm?story_id=11326188 ) with much success. We will analyze the value of this method by comparing it to similar tasks performed in laboratory experiments, both in terms of user performance and deployment costs.

- Impact: By converting the task into a simple game, we hope to reduce the problem of user fatigue. Additionally, if the game is played on a social networking site, we are able to track basic information of users who perform the tasks and, more importantly, can identify returning users. Thus, we can track not only a user's performance, but also how they improve at a given task over time.

- 3-Week Feasibility Study: As a prototype, we can select one particular task to map into a simple online game. To check for feasibility, we need to ensure that the results we get from our proposed method are similar to the results found in laboratory settings. There are two possible effects we must test for: bias in results due to the mapping into a game, and bias in results due to the sample of subjects or any change caused by the web-based component. A simple test would be to first test users in a lab using traditional methods as a baseline, and then see how performance differs from that in laboratory tests using the game-based mapping. This will determine if the game appropriately measures the given task. Next, an online version of the game can be introduced, and performance can be compared with the laboratory settings. If performance is similar in all of these tests, we have found a method for measuring low-level tasks that allows for many samples and minimal cost.

- Risks/Costs: There are no clear risks involved with this study. Potential costs would be those required for development of each experiment and for web hosting.

Specific Aims

Primary

- Filter and merge existing HCI guidelines into a comprehensive collection of rules, with specific emphasis on those guidelines that derive from cognitive principles.

- Formulate a set of cognitive models to evaluate HCI guidelines quantitatively, with respect to cognition, drawing from research in Cognitive Science and Perceptual Pyschology.

- Formulate a set of performance/usability models to evaluate HCI guidelines quantitatively, with respect to user performance, drawing from research in Human-Computer Interaction and Ubiquitous Computing.

- Analyze correlations between cognition, perception and usability, validating (?) Cognitive Science's utility in a broad HCI context.

- Through isolated experiments, determine correlations between individual cognitive/perceptual processes and usability.

- Integrate findings into a quantitative system for evaluating HCI design with respect to performance, determining design decisions that are detrimental to user performance, and offering sets of suggestions for improvement.

- Integrate findings into a real-time system that may be plugged into an existing interactive application to enhance usability.

- This quantitative system will do so by taking into account:

- User goals, as determined via interaction history.

- Performance following interruptions or shifts in user-goals (working spheres).

- Collaborative usability through sharing interaction.

- This quantitative system will do so by taking into account:

Other Application Aims

- Develop a scoring system for interfaces to evaluate the degree to which all changes and causal relations are tracked by motion cues that are contiguous in time and/or space.

- Accurately assess computational and psychological costs for tasks and subtasks. To do this, we will develop two non-trivial prototype systems; a conventional control system and a novel system which is based on our model of task switching. We will use our model to make specific predictions about relative task performance and user affect responses, and then test these predictions empirically in a formal study.

- Collect ratings of the design and cognitive principles on a range of interfaces and use this data to generate a relevance matrix.

Usability/cognition matrix

- Extract general design principles that are common across multiple sets of guidelines.

- Extract quantifiable cognitive principles that are relevant to HCI.

- Collect ratings of the design and cognitive principles on a range of interfaces and use this data to generate a relevance matrix.

- Generate specific rules for designing/assessing interfaces with regard to highly correlated pairs of design and cognitive principles.

- Investigate the possibility of using cognitive simulations to generate such assessments. E J Kalafarski 16:46, 13 March 2009 (UTC)

Background

Models of cognition

There are several models of cognition, ranging from fundamental aspects of neurological processing to extremely high-level psychological analysis. Three main theories seem to have become recognized as the most helpful in conceptualizing the actual process of HCI. These models all agree that one cannot accurately analyze HCI by viewing the user without context, but the extent and nature of this context varies greatly.

Activity Theory, developed in the early 20th century by Russian psychologists S.L. Rubinstein and A.N. Leontiev, posits the existence of four discrete aspects of human-computer interaction. The "Subject" is the human interacting with the item, who possesses an "Object" (e.g. a goal) which they hope to accomplish by using a tool. The Subject conceptualizes the realization of the Object via an "Action", which may be as simple or complex as is necessary. The Action is made up of one or more "Operations", the most fundamental level of interaction including typing, clicking, etc.

A key concept in Activity Theory is that of the artifact, which mediates all interaction. The computer itself need not be the only artifact in HCI - others include all sorts of signs, algorithmic methods, instruments, etc.

A longer synopsis of Activity Theory may be found at this website.

The Situated Action Model focuses on emergent behavior, emphasizing the subjective aspect of human-computer interaction and the therefore-necessary allowance for a wide variety of users. This model proposes the least amount of contextual interaction, and seems to maintain that the interactive experience is determined entirely by the user's ability to use the system in question. While limiting, this concept of usability can be very informative when designing for less tech-savvy users.

Distributed Cognition proposes that the computer (or, as in Activity Theory, any other artifact) can be used and ought to be thought of as an extension of the mental processing of the human. This is not to say that the two are of equal or even comparable cognitive abilities, but that each has unique strengths and that recognition of and planning around these relative advantages can lead to increased efficiency and effectiveness. The rotation of blocks in Tetris serves as a perfect example of this sort of cognitive symbiosis.

GOMS (Goals, Operators, Methods and Selection rules) is a method of HCI observation, analysis, and prediction. Developed in 1983 by Stuard Card, Thomas P. Moran, and Allan Newell, GOMS is certainly one of the best-known models of human mental processes in HCI, and has had a few notable success stories. There exist multiple versions of GOMS, each specialized for certain applications, but all follow the basic framework as follows:

- Goals are the user's achievement benchmarks, the mental constructs toward which the user works

- Operators are actions employed by the user in search of these goals

- Methods are sequences of Operators (exist at a higher level), and may include mental algorithms and other sets of instructions or patterns

While this hierarchy is well defined, the objective position of each level is not. One user's operator may equate to another's method or intermediary goal. As a result of this and other theoretical weaknesses, GOMS is not known for being a strong cognitive processing analogue but does present a parsimonious model of HCI.

(Owned by Steven)

Embodied Models of Cognition

This field of applied research straddles the divide between cognitive modeling and automated user evaluation. Embodied models are so named because they employ sensory and mechanic modules in order to simulate the process of a user's interaction with a given interface. Such models have much promise for advancing the field of automated user evaluation, but literature thus reviewed suggests that current models leave much to be desired.

Models rely on a combination of data gleaned from the interface itself and information and instructions delivered by an evaluation expert. Simulated eyes and ears can interpret stimuli from the interface, but these stimuli may have to be predefined by the expert to varying degrees, depending on the specific model and the complexity of the stimuli. Simulated hands can deliver input under the constraints of well established laws of user performance, as well as with estimated levels of error.

The imperfect nature of these interactions is both a boon and a burden. A new, interesting perspective can be gained, but it may turn out to irrelevant when considering the behavior of true humans (aka a false positive). An error may be logged in the design of a certain pane, but the appearance may in fact be highly salient for human users (aka a false negative). Minimizing these errors is a difficult task, and it may prove to be quite a long time before embodied models can surpass other forms of automated evaluation.

Embodied models do offer a few undeniable benefits, however. They can evaluate interfaces at an early level which would otherwise not be fiscally justifiable. They can also continue to evaluate interfaces at the designer's leisure - at any hour and for any duration. While these tasks may also be accomplished by other automated evaluation tools, embodied models require preparatory minimal effort on the part of the designer.

For several reasons however, not the least of which is the difficulty in defining the detail level at which an interface ought to operate, embodied models are unlikely to become substitutes for human subjects in the near future.

(Owned by Steven)

Workflow Context

There are, at least, two levels at which users work (Gonzales, et al., 2004). Users accomplish individual low-level tasks which are part of larger working spheres; for example, an office worker might send several emails, create several Post-It (TM) note reminders, and then edit a word document, each of these smaller tasks being part of a single larger working sphere of "adding a new section to the website." Thus, it is important to understand this larger workflow context - which often involves extensive levels of multi-tasking, as well as switching between a variety of computing devices and traditional tools, such as notebooks. In this study it was found that the information workers surveyed typically switch individual tasks every 2 minutes and have many simultaneous working spheres which they switch between, on average every 12 minutes. This frenzied pace of switching tasks and switching working spheres suggests that users will not be using a single application or device for a long period of time, and that affordances to support this characteristic pattern of information work are important.

Czerwinski, et al. conducted a diary study of task switching and interruptions of users in 2004. This study showed that task complexity, task duration, length of absence, and number of interruptions all affected the users' own perceived diffculty of switching tasks. Iqbal, et al. studied task disruption and recovery in a field study, and found that users often visited several applications as a result of an alert, such as a new email notification, and that 27% of task suspensions resulted in 2 hours or more of disruption. Users in the study said that losing context was a significant problem in switching tasks, and led in part to the length of some of these disruptions. This work hints at the importance of providing cues to users to maintain and regain lost context during task switching.

(Andrew Bragdon - OWNER)

The problem of task switching is exacerbated when some tasks are more routine than others. When a person intends to switch from a routine task to a novel task at some later time, they often forget the context of the original task (Aarts et al., 1999). Also, if both tasks are done in the same context, with the same tools or with the same materials, people have difficulty inhibiting the routine task while doing the novel task (Stroop, 1935). This inhibition also makes switching back to the routine task slower (Allport et al., 1994). All of these problems can be alleviated to some degree by salient cues in the environment. Enacting the intention to switch becomes easier when there is a salient reminder at the appropriate time (McDaniel and Einstein, 1993) and associating different environmental cues with different goals can automatically trigger appropriate behavior (Aarts and Dijksterhuis, 2003).

(Adam)

(Edited by Andrew)

Qunatitative Models: Fitts's law, Steering Law

Fitts's law and the steering law are examples of quantiative models that predict user performance when using certain types of user interfaces. In addition to these classic models, Cao and Zhai developed and validated a quantitative model of human performance of pen stroke gestures in 2007. Lank and Saund utilized a model which used curvature to predict the speed of a pen as it moved across a surface to help disambiguate target selection intent.

In addition, quantitative models are often tested against new interfaces to verify that they hold. For example, Grossman et al. verified that their Bubble Cursor approach to enlarging effective pointing target sizes obeyed Fitts's law for actual distance traveled.

In addition to formal models, machine learning techniques have been applied to modeling user interaction as well. For example, Hurst, et al., used a learning classifier, trained on low-level mouse and keyboard usage patterns, to identify novice and expert users dynamically with accuracies as high as 91%. This classifier was then used to provide different information and feedback to the user as appropriate.

(Andrew Bragdon - OWNER)

Distributed cognition

Distributed cognition is a theory in which thoughts take place in and outside of the brain. Human's have a great ability to use tools and to incorporate their environments into their sphere of thinking. Clark puts it nicely in [Clark-1994-TEM].

Therefore, optimal configurations when considering HCI design will treat the brain, person, interface, and computer as a holistic system comprising cognitions.

In practical terms, the issue at hand for our proposal is how to best maximize utility by distributing the cognitive tasks at hand to different components of the whole system. Simply, which tasks can we off-load to the computer to do for us, faster and more accurately? What tasks should we purposely leave the computer out of?

Typically, those tasks most eligible to be off-loaded are the ones which we perform poorly on. Conveniently, the tasks which computers perform poorly on we excel at. Here are a few examples:

- Computer's Area of Expertise: number crunching, memory, logical reasoning, precise

- Human's Area of Expertise: Associative thought, real-world knowledge, social behavior, alogical reasoning, imprecise

Using this division of cognitive labor allows us to optimize task work flows. Ignoring it puts strain and bottlenecks at either the computer, the human, or the interface. The field of HCI is full of examples of failures which can be attributed to not recognizing which tasks should be handled by which sub-system.

As a heuristic to divide thinking, one might turn to the dual-process theory literature Evans-2003-ITM. What is most often called System 1 is what human's are good at, while System 2 tasks are what computers do well.

This type of distribution has recently been addressed (e.g. Griffith-NSD-2007) and a framework based on distributed cognition has also been proposed (Hollan-2000-DCF), though in only a broad sense. More concrete models have also been proposed in past years (http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.57.2043).

(Owner - Gideon)

Information Processing Approach to Cognition

The dominant approach in Cognitive Science is called information processing. It sees cognition as a system that takes in information from the environment, forms mental representations and manipulates those representations in order to create the information needed to achieve its goals. This approach includes three levels of analysis originally proposed by Marr (will cite):

- Computational - What are the goals of a process or representation? What are the inputs and desired outputs required of a system which performs a task? Models at this level of analysis are often considered normative models, because any agent wanting to perform the task should conform to them. Rational agent models of decision making, for example, belong at this level of analysis.

- Process/Algorithmic - What are the processes or algorithms involved in how humans perform the task? This is the most common level of analysis as it focuses on the mental representations, manipulations and computational faculties involved in actual human processing. Algorithmic descriptions of human capabilities and limitations, such as working memory size, belong at this level of analysis.

- Implementation - How are the processes and algorithms be actual biological computation? Dopamine theories of reward learning, for example, belong at this level of analysis.

The information processing approach is often contrasted with the distributed cognition approach. Its advantage is that it finds general mechanisms that are valid across many different contexts and situations. Its disadvantage is that it can have difficulty explaining the rich interactions between people and their environment.

In considering users as information processors, interfaces should take into account people's computational limitations on short term memory, learning and vision as well as the algorithms and representations that they use to process information and pursue goals.

(Adam)

Models of perception

The Ecological Approach to Perception

Gibsonianism, named after James J. Gibson and more commonly referred to as ecological psychology, is an epistemological direct realist theory of perception and action. It is often contrasted to information processing and cognitivist approaches which generally assume that perception is a constructive process operating on impoverished sense-data inputs (e.g. photoreceptor activity) to generate representations of the the world with added structure and meaning (e.g. a mental or neural "picture" of a chair), ecological psychology treats perception as direct, non-inferential, unmediated (by retinal images or mental representations) epistemic contact with behaviorally-relevant features of the environment (Warren, 2005). The possibilities for action that the environment offers a given animal are taken to be specified by the co-perception of self (e.g. proprioception) and information available in structured energy distributions (e.g. the optic array of light arriving at the eyes), and these possibilities for action constitute the affordances of the environment with respect that animal (Gibson, 1986).

The notion of affordances has proven to be a very useful concept in HCI, however, some of its original meaning has been lost in translation. For example, it is worth noting that the Gibson's definition of affordances emphasizes possibilities for action and not their relative likelihoods. For example, for most humans, laptop computer screens afford puncturing with Swiss Army knives, however, it is unlikely that a user will attempt to retrieve an electronic coupon by carving it out of their monitor. This example illustrates that interfaces often afford a class of actions that are undesirable from the perspective of both the designer and the user. Following Norman (1999), discovery of some affordances (e.g. that clicking the send button affords sending an email) may require that the user understand certain conventions (e.g. that moving the mouse pointer to an on-screen button and clicking the mouse will depress that on-screen button). Therefore, the role of the interface designer should be to make task-relevant affordances either apparent or else discoverable through exploration of the interface, or else employ some means of adaptively aiding the user in discovering the task-relevant affordances that the interface offers.

Design guidelines

A multitude of rule sets exist for the design of not only interface, but architecture, city planning, and software development. They can range in scale from one primary rule to as many Christopher Alexander's 253 rules for urban environments,[1] which he introduced with the concept design patterns in the 1970s. Study has likewise been conducted on the use of these rules:[2] guidelines are often only partially understood, indistinct to the developer, and "fraught" with potential usability problems given a real-world situation.

Application to AUE

And yet, the vast majority of guideline sets, including the most popular rulesets, have been arrived at heuristically. The most successful, such as Raskin's and Schneiderman's, have been forged from years of observation instead of empirical study and experimentation. The problem is similar to the problem of circular logic faced by automated usability evaluations: an automated system is limited in the suggestions it can offer to a set of preprogrammed guidelines which have often not been subjected to rigorous experimentation.[3] In the vast majority of existing studies, emphasis has traditionally been placed on either the development of guidelines or the application of existing guidelines to automated evaluation. A mutually-reinforcing development of both simultaneously has not been attempted.

Overlap between rulesets is inevitable and unavoidable. For our purposes of evaluating existing rulesets efficiently, without extracting and analyzing each rule individually, it may be desirable to identify the the overarching principles or philosophy (max. 2 or 3) for a given ruleset and determining their quantitative relevance to problems of cognition.

Popular and seminal examples

Schneiderman's Eight Golden Rules date to 1987 and are arguably the most-cited. They are heuristic, but can be somewhat classified by cognitive objective: at least two rules apply primarily to repeated use, versus discoverability. Up to five of Schneiderman's rules emphasize predictability in the outcomes of operations and increased feedback and control in the agency of the user. His final rule, paradoxically, removes control from the user by suggesting a reduced short-term memory load, which we can arguably classify as simplicity.

Raskin's Design Rules are classified into five principles by the author, augmented by definitions and supporting rules. While one principle is primarily aesthetic (a design problem arguably out of the bounds of this proposal) and one is a basic endorsement of testing, the remaining three begin to reflect philosophies similar to Schneiderman's: reliability or predictability, simplicity or efficiency (which we can construe as two sides of the same coin), and finally he introduces a concept of uninterruptibility.

Maeda's Laws of Simplicity are fewer, and ostensibly emphasize simplicity exclusively, although elements of use as related by Schneiderman's rules and efficiency as defined by Raskin may be facets of this simplicity. Google's corporate mission statement presents Ten Principles, only half of which can be considered true interface guidelines. Efficiency and simplicity are cited explicitly, aesthetics are once again noted as crucial, and working within a user's trust is another application of predictability.

Elements and goals of a guideline set

Myriad rulesets exist, but variation becomes scarce—it indeed seems possible to parse these common rulesets into overarching principles that can be converted to or associated with quantifiable cognitive properties. For example, it is likely simplicity has an analogue in the short-term memory retention or visual retention of the user, vis a vis the rule of Seven, Plus or Minus Two. Predictability likewise may have an analogue in Activity Theory, in regards to a user's perceptual expectations for a given action; uninterruptibility has implications in cognitive task-switching;[4] and so forth.

Within the scope of this proposal, we aim to reduce and refine these philosophies found in seminal rulesets and identify their logical cognitive analogues. By assigning a quantifiable taxonomy to these principles, we will be able to rank and weight them with regard to their real-world applicability, developing a set of "meta-guidelines" and rules for applying them to a given interface in an automated manner. Combined with cognitive models and multi-modal HCI analysis, we seek to develop, in parallel with these guidelines, the interface evaluation system responsible for their application. E J Kalafarski 15:21, 6 February 2009 (UTC)

User interface evaluations

Interaction capture

Yi et. al. have performed a survey of the visualization literature and categorized different types of interactions that users were faced with. They are as follows:

- Select: mark something as interesting

- Explore: show me something else

- Reconfigure: show me a different arrangement

- Encode: show me a different representation

- Abstract/Elaborate: show me more or less detail

- Filter: show me something conditionally

- Connect: show me related items

Different GUI components may be able to perform the same type of interaction. We would like to categorize GUI components or patterns that are used bring about these interactions. We then have a library of components we can use to complete a given task. The goal is to create components for a given interaction that can minimize cost to the user. Because the cost of a component is likely dependent on the other components used, the goal of the designer might be to choose a combination of components that minimizes this cost. To do this, we need a way to measure costs, which is discussed in the next section.

Cost-based analyses

In A Framework of Interaction Costs in Information Visualization, Lam performs a survey of 32 user studies and classifies several types of costs that can be used for qualitative interface evaluation. The classification scheme is based on Donald Norman's Seven Stages of Action from his book, The Design of Everyday Things (summary).

- Decision costs: How does user performance decrease when there is an overwhelming amount of data to observe or too many possible actions to take.

- System-power costs: How does the user translate a high-level goal into a sequence of allowable actions by the interface?

- Multiple input mode costs: Cost of providing an action selection system that is not unified, for example, if there is one button that does two different things, depending on context.

- Physical-motion costs: Physical cost to the user to interact with the interface, for example, measuring mouse movement costs with Fitts' Law.

- Visual-cluttering costs: Cost due to unwanted visual distractions, such as a mouse hovering pop-up occluding part of the screen.

- View- and State-change costs: when the user causes the interface to change views, this new view should be consistent with the old one, in that it should meet the users expectations of where things should be in the new view, based on his knowledge of the old one.

Evaluation in practice

User interfaces are usually evaluated in practice using two methods: usability inspection methods, where a programmer or one or more experts evaluates the interface through inspection; or usability testing, where empirical tests are performed with some group of naive human users. Some usability inspection methods include Cognitive walkthrough, Heuristic evaluation, and Pluralistic walkthrough. While these inspection methods do not using naive human subjects, the details of the methods might be useful in helping to formalize what interactions are made between a user and an interface, and what each interactions' costs are for a given design.

Jeffries et. al. provide a real-world comparison between two of the usability inspection methods (heuristic evaluation and cognitive walkthrough), the usability testing method, as well as following some published software guidelines for interface design.

Multimodal HCI

Continued advancements in several signal processing techniques have given rise to a multitude of mechanisms that allow for rich, multimodal, human-computer interaction. These include systems for head-tracking, eye- or pupil-tracking, fingertip tracking, recognition of speech, and detection of electrical impulses in the brain, among others Sharma-1998-TMH. With ever-increasing computing power, integrating these systems in real-time applications has become a plausible endeavor.

Head-tracking

- In virtual, stereoscopic environments, head-tracking has been exploited with great success to create an immersive effect, allowing a user to move freely and naturally while dynamically updating the user’s viewpoint in a visual environment. Head-tracking has been employed in non-immersive settings as well, though careful consideration must be paid to account for unintended movements by the user, which may result in distracting visual effects.

Pupil-tracking

- Pupil-tracking has been studied a great deal in the field of Cognitive Science ... (need some examples here from CogSci). In the HCI community, pupil-tracking has traditionally been used for posterior analysis of interface designs, and is particularly prevalent in web interface design. An alternative utility of pupil-tracking is to employ it in real-time as an actual mode of interaction. This has been examined in relatively few cases (citations), where typically the eyes are used to control a cursor onscreen. Like head-tracking, implementations of pupil-tracking must be conscious of unintended eye-movements, which are incredibly frequent.

Fingertip-tracking, Gestural recognition

- Fingertip tracking and gestural recognition of the hands are the subjects of much research in the HCI community, particularly in the Virtual Environment and Augmented Reality disciplines. Less implicit than head or pupil-tracking, gestural recognition of the hands may draw upon the wealth of precedents readily observed in natural human interactions. As sensing technologies become less obtrusive and more robust, this method of interaction has the potential to become quite effective.

Speech Recognition

- Speech recognition is becoming much better, though effective implementation of its desired effects is non-trivial in many applications. (More on this later).

Brain Activity Detection

- The use of electroencephelograms (EEGs) in HCI is quite recent, and with limited degrees of freedom, few robust interfaces have been designed around it. Some recent advances in the pragmatic use of EEGs in HCI research can be seen in Grimes et al. The possibility of using brain function to interface with a machine is cause for great excitement in the HCI community, and further advances in non-invasive techniques for accessing brain function may allow teleo-HCI to become a reality.

In sum, the synchronized usage of these modes of interaction make it possible to architect an HCI system capable of sensing and interpreting many of the mechanisms humans use to transmit information among one another. (Trevor)

Workflow analysis

Research in workflow and interaction analysis remains relatively sparse, though its utility would appear to be many-fold. Tools for such analysis have the potential to facilitate data navigation, provide search mechanisms, and allow for more efficient collaborative discovery. In addition, awareness and caching of interaction histories readily allows for explanatory presentations of results, and has the potential to provide training data for machine learning mechanisms.

Workflow/Interaction Capture

- VisTrails is an optimized workflow system developed at the Sci Institute at the University of Utah, and implemented within their VTK visualization package. The primary purpose of the system is to increase performance when working with multiple visualizations simultaneously. This is accomplished by storing low-level workflow processes to reduce computational redundancy. Three papers on VisTrails can be found here: Callahan-2006-MED, Callahan-2006-VVM, Bavoil-2005-VEI

- If you want to check out some of Trevor's work having to do with using interaction histories in 3D, time-varying scientific visualizations, his preliminary work that was presented at Vis '08 can be seen here: Abstract, Poster

- Jeff Heer of Stanford (formerly Berkley) has presented work on using Graphical Interaction Histories within the Tableau InfoVis application. Though geared toward two-dimensional visualizations with clearly defined events, his work offers some very useful design guidelines for working with interaction histories, including some evaluation from the deployment of his techniques within Tableau.

Workflow/Interaction Prediction

- A help system for Microsoft Office that is based on interaction histories and Dynamic Bayes Nets.

- Introduces the notion of Relational Markov Models (RMMs), a construct that extends traditional Markov Models by imposing a relational hierarchy on the state space. This abstraction allows for learning and inference on very large state spaces with only sparse training data. These methods are evaluated with respect to Adaptive Web Interfaces, but I believe the general RMM idea can be applied in many other HCI settings.

- Learning Dynamic Bayesian Networks

- Relational Hidden Markov Models (powerpoint)

- COLLAGEN: A Collaboration Manager for Software Interface Agents

- User Modeling via Stereotypes

- User Modeling and Adaptive Navigation Support in WWW-Based Tutoring Systems

- User Modeling Inc.

- A site dedicated to user modeling, with links to conferences, journals, and other materials.

Interface Improvements

(INCOMPLETE)

Significance

While attempts have been made in the past to apply cognitive theory to the task of developing human-computer interfaces, there remains much work to be done. No standard and widespread model for cognitive interaction with a device exists. The roles of perception and cognition, while examined and studied independently, are often at odds with empirical and successful design guidelines in practice. Methods of study and evaluation, such as eye-tracking and workflow analysis, are still governed primarily by the needs at the end of the development process, with no quantitative model capable of influencing efficiency and consistency in the field.

We demonstrate in wide-ranging preliminary work that cognitive theory has a tangible and valuable role in all the stages of interface design and evaluation: models of distributed cognition can exert useful influence on the design of interfaces and the guidelines that govern it; algorithmic workflow analysis can lead to new interaction methods, including predictive options; a model of human perception can greatly enhance the usefulness of multimodal user study techniques; a better understanding of why classical strategies work will bring us closer to the "holy grail" of automated interface evaluation and recommendation. We can bring the field further down many of the only partially-explored avenues of the field in the years ahead.

The disparate elements of our proposed works are the building blocks of a cohesive theoretical understanding of the role cognition is capable of playing. As a demonstration of the feasibility of a more complete, multi-year investigation, these elements have been specifically selected to show the opportunities of integration throughout the interface development process. We construct an architecture of this preliminary work, showing the relationships of these components and how they construct a foundation for further substantial work. E J Kalafarski 14:06, 3 April 2009 (UTC)

At the crux is an explicit and quantifiable mapping between existing accepted design rules and the cognitive principles we believe underlie them. This narrow yet comprehensive and extensible "gateway" between the theoretical and practical domains of HCI allows for the pursuit of advanced work on either side of this spectrum and provides an avenue for the linking of complementary results, across this domain boundary, as they emerge. In the domain of cognition, the psychological theory of distributed cognition is applied rigorously to the problem of task-assignment and the standardized division of labor at the interface level; this, in turn, is used to influence a broader theory of cognition in usability science that will be applied strongly and to a growing degree across the domain boundary. These theoretical underpinnings are governed strongly by the bleeding edge of cognitive science, but with a watchful and tangible eye on the pragmatic applications to which they will lead

On the other side of the domain boundary, we have demonstrated the feasibility of and intend to pursue specific, focused problems in the field of practical usability, likewise influenced and influencing the cognitive work on the opposite end of the spectrum. These avenues include the pursuit of interaction histories and their potential role in a predictive suite of usability tools, and support interfaces for the problem of task-interruption.

With this project architecture, we seek the unfettered and "domain-specific" pursuit of "hard" problems both in the cognitive and practical usability domains. At the same time, however, we have provided an explicit, quantified manner of extending principles and techniques that emerge in either of these domains into the other. This symmetric approach supports our fundamental assumption that despite theoretical underpinnings that have evolved independently, the cognitive aspects of HCI and empirical observation in the field of usability over the last 20 years are governed by the same computational and psychological forces, and can thus be related and developed in parallel to greater efficiency and effect. E J Kalafarski 14:06, 3 April 2009 (UTC)

Preliminary results

Gideon

Extending CPM-GOMS: The need to dichotemize cognition

A meta-analysis of a representative subset of the cognitive psychology and human-computer interaction literature presents evidence that there is a beneficial distinction that can be made between two different systems of thought that together comprise cognition. These two systems are explicated in what is most commonly referred to as Dual-Process or Dual-System Theory. Just as the CPM-GOMS model makes a distinction between, for example, perception and cognition, we claim that an equally crucial distinction must be made between System 1 (low-level) and System 2 (high-level) cognition.

Our analysis of 500 papers in these fields gives us the necessary foundation to elaborate on the cognitive module in the CPM architecture. We apply our new model to the task of a scientific visualization software package, and compare model predictions to those of the current CPM-GOMS model. Our results result in not only a more accurate assessment of time, but a finer-grained analysis of workflow, and a better understanding of parralellization in HCI task modeling.

Steven

Preliminary Results:

Redone Week 1 Results

- Problem: The current state of cognitive HCI theory is both deeply conflicted and antiquated. We have carefully examined the existing literature and began developing a more modern, applicable, and empirically proven conceptualization of the interaction itself.

Preliminary Work:

- A literature review of the leading cognitive HCI theories, with special attention paid to activity theory and subjective realities.

- The development of a common vocabulary with which to describe the components of each of these theories, to facilitate both understanding and to discern applicability to the current digital environment. This lexicon is then used to define the intuitive merits of each approach and isolate them as contributing factors for the eventual theory. This segment required 30 hours of research.

- Task-oriented user studies are conducted to distill the users’ progression of goal development and execution. Users are asked to describe their actions when viewing a recording at a later session, and these descriptions are analyzed to compile a list of working adjectives which users might use to describe their actions (in contrast with those used by developers). A factor analysis produces the most salient terms, which are linked to those derived in the 30 hour project.

- These studies are also used as the proof-of-concept of the development of a descriptive model against which the prescriptive theory will be measured.

Week 2 Results

- We have developed a skeleton of the hybrid cognitive HCI theory, along with descriptions of the sources of each component and relevant citations. This skeleton has been compared to the descriptive data gained from the above trials, as well as additional user trials based upon the insight gained from these original comparisons. The skeleton presents a foundation upon which we can begin to describe not merely the stages in a user’s task conception and completion but the more pertinent transition between these stages. We have thus begun to correlate semantic data from user trials with the theory’s stages and created a framework in which to present empirical evidence of the theory’s viability.

Week 3 Results

- We have, with high validity, correlated several semantic variables with initial goal formation stages of the framework - establishing a proof of concept which may be extended to its other stages. Having established a wide bank of terms, we are in the process of contacting subjects and replaying their footage to posit substitute terms in order to facilitate consolidation of common actions and declarations. This process is likely to be quite lengthy, but the nature of the design allows the validity of the framework to increase its real-world relevance with every piece of data gathered.

Trevor and Eric

Interaction Histories

Project idea: Generating interaction histories within scientific visualization applications to facilitate individual and collaborative scientific discovery.

Preliminary Work

- A software infrastructure for caching and filtering interaction events has been developed within an existing scientific application aimed at exploring animal kinematic data captured via high-speed x-ray and CT.

- Methods for visualizing, editing, and sharing interaction histories have been designed and implemented.

- Methods for annotating and querying interactions have been implemented.

Preliminary Work from the Future

- Software model extended to two other interactive visualizations -- a flow visualization application, and a protein visualization application.

- User study to examine techniques for automatic history generation

- Automatic creation v. semi-automatic creation v. manual creation

- Timed-task pilot study performed to validate utility of interaction history techniques

- Task performance with histories v. without histories

General Outline of Tasks

- Capture user interaction history

- Predict user interactions, given interaction history

- Use a relational markov model?

- Modify the UI, given predicted user interactions

- Evaluate this modified UI

- Compare performance with and without UI modifications

- Evaluate performance when predicted interactions are incorrect x% of the time

Jon

We have developed a model of human cognitive and perceptual abilities that allows us to predict human performance and thereby converge on ideal interfaces while simultaneously ruling out sub-optimal ones. The model consists of a set of design principles combined with an extensive catalog of human perceptual and cognitive constraints on interface design. The effectiveness of this model has been demonstrated by using the combined set of principles to assign scores to a set of GUIs designed to help a user accomplish the same overarching task, and comparing those scores with actual user performance.

Ian

We know that applications are able to automatically gauge user’s expertise with the program and automatically alter the experience to their skill level with continuous usage. We have developed a list of criteria to be monitored with the intention of automatically determining a user’s level of expertise and correspondingly present an appropriate interface with which the user is presented.

Humans often are confounded by new and unfamiliar displays and interfaces when confronted with them for the first time. What we are proposing is a daemon which constantly will monitor user progress on a variety of dimensions to be used by applications to then, based on principles of learning and memory, provide the user with a seamless and unobtrusive “live” interface with the intention of painlessly learning complicated tasks and interfaces.

Eric

Project idea: Introduce a method for collecting data on user performance in cognitive, perceptual, and motor-control tasks that requires less monetary cost, allows for a greater number of samples, and measures user improvements over time.

Preliminary Work Create a simple "brain training"-style game in which users must perform a simple cognitive task. As an example, perhaps the task is to manipulate shape1 into shape2, given a simple set of operators. Each of the users actions (mouse movements, button clicks, etc.) will be documented along with the state of the game at that time. By varying the interface for different users, we can see how it affects performance in terms of cognitive and low-level tasks.

Preliminary tests will first measure user performance in a laboratory setting. We will run subjects on two different interfaces and compare the differences in performance. We will then perform this same test in an online setting, and will evaluate how performance differs in this case, which is more subject to user interruptions and noisy data. If performance is similar in all of these tests, we have found a method for measuring low-level tasks that allows for many samples and minimal cost. If performance differs greatly, it may be that the amount of noise introduced by users playing in a casual setting may make the project infeasible.

Andrew Bragdon

I. Goals

The goals of the preliminary work are to gain qualitative insight into how information workers practice metawork, and to determine whether people might be better-supported with software which facillitates metawork and interruptions. Thus, the preliminary work should investigate, and demonstrate, the need and impact of the core goals of the project.

II. Methodology

Seven information workers, ages 20-38 (5 male, 2 female), were interviewed to determine which methods they use to "stay organized". An initial list of metawork strategies was established from two pilot interviews, and then a final list was compiled. Participants then responded to a series of 17 questions designed to gain insight into their metawork strategies and process. In addition, verbal interviews were conducted to get additional open-ended feedback.

III. Final Results

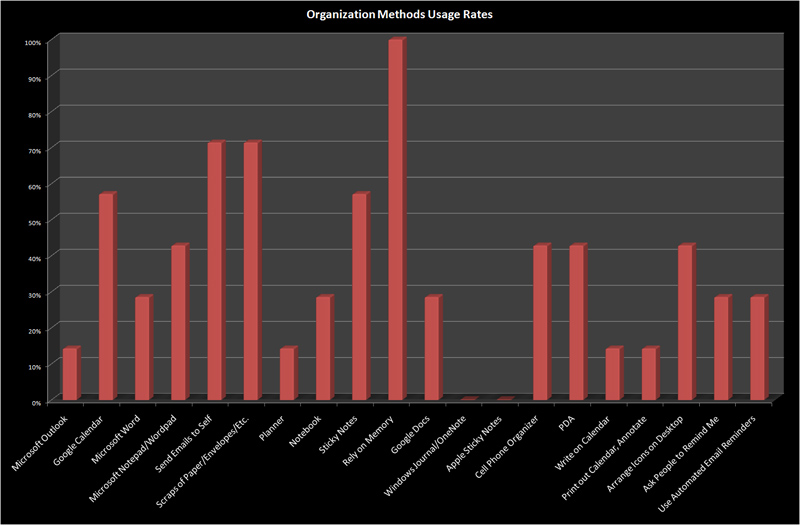

A histogram of methods people use to "stay organized" in terms of tracking things they need to do (TODOs), appointments and meetings, etc. is shown in the figure below.

In addition to these methods, participants also used a number of other methods, including:

- iCal

- Notes written in xterms

- "Inbox zero" method of email organization

- iGoogle Notepad (for tasks)

- Tag emails as "TODO", "Important", etc.

- Things (Organizer Software)

- Physical items placed to "remind me of things"

- Sometimes arranging windows on desk

- Keeping browser tabs open

- Bookmarking web pages

- Keep programs/files open scrolled to certain locations sometimes with things selected

In addition, three participants said that when interrupted they "rarely" or "very rarely" were able to resume the task they were working on prior to the interruption. Three of the participants said that they would not actively recommend their metawork strategies for other people, and two said that staying organized was "difficult".

Four participants were neutral to the idea of new tools to help them stay organized and three said that they would like to have such a tool/tools.

IV. Discussion

These results qunatiatively support our hypothesis that there is no clearly dominant set of metawork strategies employed by information workers. This highly fragemented landscape is surprising, even though most information workers work in a similar environment - at a desk, on the phone, in meetings - and with the same types of tools - computers, pens, paper, etc. We believe that this suggests that there are complex tradeoffs between these methods and that no single method is sufficient. We therefore believe that users will be better supported with a new set of software-based metawork tools.

Usability/cognition matrix

We have demonstrated the feasibility of mapping and quantifying the relationships between established design principles and a preliminary set of cognitive principles. By assigning specific rules for the evaluation and development of interfaces to these relations, we've begun the construction of a larger and more concrete set of design guidelines. Although the work here is based on manually-generated user ratings, we describe how the continuing development of this framework would incorporate more advanced and automated data collection. We've provided the foundations for continuing work towards a unified method of systematic, and in some cases automated, interface evaluation.

EJ

Problem: There currently exists no metric for evaluating interfaces that attempts to reconcile popular and successful heuristic design guidelines with cognitive theory.

Preliminary Work

I. A mapping of empirically-effective heuristic design guidelines to fundamental cognitive principles.

- A set of "common" design guidelines is arrived at through survey of popular and effective heuristic guidelines in use.

- Proposed common design principles:

Discoverability Flexibility Appropriate visual presentation Predictability Consistency Simplicity Memory load reduction Feedback Task match User control Efficiency

- Proposed cognitive principles:

Affordance Visual cue Cognitive load Chunking Activity Actability

II. A weighting or priority for each of these analogues.

- These can begin as binary estimations based on empirical evidence.

- Through experimentation, these values should converge to discrete priority values for each analogue, allowing a ranking of analogues.

III. A system for applying these analogues and respective priority to the evaluation of an interface.

- This can occur manually or in an automated fashion.

- In this step (or possibly in a separate step), analogues should be assigned a suggestion or potential correction to provide in the event of "failure" of a particular test by a given interface.

Adam Darlow

I. Goals

A. Evaluate the interactions between various cognitive principles and design principles. There are three basic relations:

1. The cognitive principle is the motivation behind the design principle. 2. The cognitive principle suggests a method for achieving the design principle. 3. The cognitive principle and design principle are unrelated. (Hopefully few)

B. Make design rules which are suggested by the combination of a cognitive principle and a design principle.

II. Description of methodology/experimental procedure

A. Collecting commonly accepted design principles from the literature on interface design and well established cognitive principles from the cognitive psychology literature and constructing a matrix which crosses them. Most squares in the matrix should suggest specific design rules.

III. Results

As a preliminary effort, I have chosen the following two cognitive principles and three design principles:

Cognitive principles

- C1. People derive complex associations and causal interpretations from temporal correlations and patterns.

- C2. People have limited working memory (7 +- 2), but each space can hold a chunk of related information.

Design Principles (from Maeda (TBD link))

- D1. Achieve simplicity through thoughtful reduction.

- D2. Organization makes a system of many appear fewer.

- D3. Knowledge makes everything simpler.

The resulting matrix entries are as follows:

- C1 + D1. Remove extraneous correlations. Things shouldn't consistently and apparently change or happen in conjunction unless they are actually related and their relation is important to the user.

- C1 + D2. Use temporal and spatial contiguity to help users organize and group multiple events meaningfully.

- C1 + D3. Use temporal correlations to effectively teach the important causal relations inherent in the interface.

- C2 + D1. Reduce the interface such that a user has to be aware of no more than 5 items simultaneously.

- C2 + D2. Groups of semantically related items can for many purposes be treated as a single item.

- C2 + D3. Teach users how things are related so that it can be chunked.

V. Conclusion

VI. Future Directions

To expand the matrix and evaluate the resulting design rules.

Research plan

We can speculate here about the details of a longer-term research plan, but it may not be necessary to actually flesh out this part of the "proposal". There does need to be enough to define what the overall proposed work is, but that may show up in earlier sections.

Usability/cognition matrix

We plan to select or create a varied set of interfaces for the same or similar tasks and ask users questions relating independently to both the chosen usability principles and cognitive principles, with the intent of using a machine learning algorithm to estimate the correlations between each cognitive principle and each design principle. For each highly-correlated pair, we will extract a design rule or suggestion based on both principles. E J Kalafarski 16:54, 13 March 2009 (UTC)

Cognitive principles

- 7 plus-or-minus-two/cognitive load

- visual pop-out

- temporal and spacial contiguity

- queued recall

- affordance

Design principles

- appropriate visual presentation

- memory-load reduction

- consistency

- control

- discoverability

References

- ↑ http://hci.rwth-aachen.de/materials/publications/borchers2000a.pdf

- ↑ http://stl.cs.queensu.ca/~graham/cisc836/lectures/readings/tetzlaff-guidelines.pdf

- ↑ http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2000/CSD-00-1105.pdf

- ↑ http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=985692.985715&coll=Portal&dl=ACM&CFID=21136843&CFTOKEN=23841774