CS295J/Research proposal (draft 2): Difference between revisions

| Line 229: | Line 229: | ||

= Preliminary Results = | = Preliminary Results = | ||

'' | ===Workflow, Multi-tasking, and Interruption=== | ||

====I. '''Goals'''==== | |||

The goals of the preliminary work are to gain qualitative insight into how information workers practice metawork, and to determine whether people might be better-supported with software which facillitates metawork and interruptions. Thus, the preliminary work should investigate, and demonstrate, the need and impact of the core goals of the project. | |||

====II. '''Methodology'''==== | |||

Seven information workers, ages 20-38 (5 male, 2 female), were interviewed to determine which methods they use to "stay organized". An initial list of metawork strategies was established from two pilot interviews, and then a final list was compiled. Participants then responded to a series of 17 questions designed to gain insight into their metawork strategies and process. In addition, verbal interviews were conducted to get additional open-ended feedback. | |||

====III. '''Final Results'''==== | |||

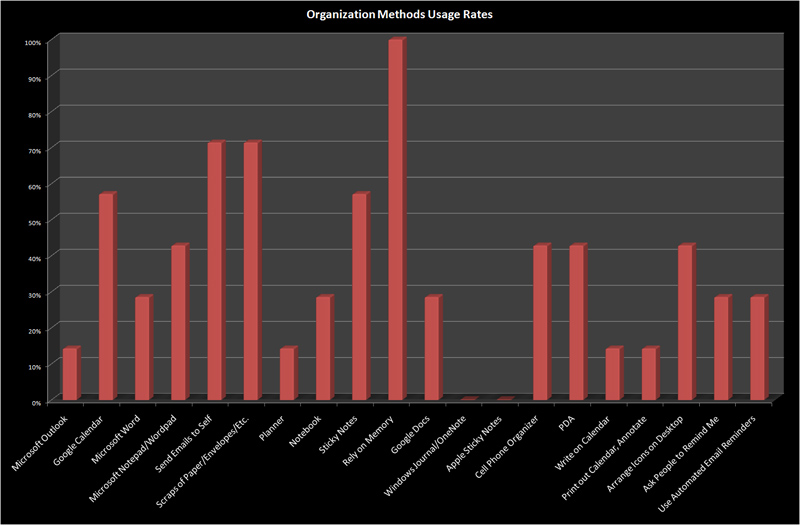

A histogram of methods people use to "stay organized" in terms of tracking things they need to do (TODOs), appointments and meetings, etc. is shown in the figure below. | |||

[[Image:AcbGraph.jpg]] | |||

In addition to these methods, participants also used a number of other methods, including: | |||

* iCal | |||

* Notes written in xterms | |||

* "Inbox zero" method of email organization | |||

* iGoogle Notepad (for tasks) | |||

* Tag emails as "TODO", "Important", etc. | |||

* Things (Organizer Software) | |||

* Physical items placed to "remind me of things" | |||

* Sometimes arranging windows on desk | |||

* Keeping browser tabs open | |||

* Bookmarking web pages | |||

* Keep programs/files open scrolled to certain locations sometimes with things selected | |||

In addition, three participants said that when interrupted they "rarely" or "very rarely" were able to resume the task they were working on prior to the interruption. Three of the participants said that they would not actively recommend their metawork strategies for other people, and two said that staying organized was "difficult". | |||

Four participants were neutral to the idea of new tools to help them stay organized and three said that they would like to have such a tool/tools. | |||

====IV. '''Discussion'''==== | |||

These results qunatiatively support our hypothesis that there is no clearly dominant set of metawork strategies employed by information workers. This highly fragemented landscape is surprising, even though most information workers work in a similar environment - at a desk, on the phone, in meetings - and with the same types of tools - computers, pens, paper, etc. We believe that this suggests that there are complex tradeoffs between these methods and that no single method is sufficient. We therefore believe that users will be better supported with a new set of software-based metawork tools. | |||

= [Criticisms] = | = [Criticisms] = | ||

Revision as of 09:05, 24 April 2009

Introduction

- Owners: Adam Darlow, Eric Sodomka, Trevor

Propose: The design, application and evaluation of a novel, cognition-based, computational framework for assessing interface design and providing automated suggestions to optimize usability.

Evaluation Methodology: Our techniques will be evaluated quantitatively through a series of user-study trials, as well as qualitatively by a team of expert interface designers.

Contributions and Significance: We expect this work to make the following contributions: 1. design-space analysis and quantitative evaluation of cognition-based techniques for assessing user interfaces. 2. design and quantitative evaluation of techniques for suggesting optimized interface-design changes. 3. an extensible, multimodal software architecture for capturing user traces integrated with pupil-tracking data, auditory recognition, and muscle-activity monitoring. (there may be more here, like testing different cognitive models, generating a markup language to represent interfaces, maybe even a unique metric space for interface usability)

--

We propose a framework for interface evaluation and recommendation that integrates behavioral models and design guidelines from both cognitive science and HCI. Our framework behaves like a committee of specialized experts, where each expert provides its own assessment of the interface, given its particular knowledge of HCI or cognitive science. For example, an expert may provide an evaluation based on the GOMS method, Fitts's law, Maeda's design principles, or cognitive models of learning and memory. An aggregator collects all of these assessments and weights the opinions of each expert, and outputs to the developer a merged evaluation score and a weighted set of recommendations.

Systematic methods of estimating human performance with computer interfaces are used only sparsely despite their obvious benefits, the reason being the overhead involved in implementing them. In order to test an interface, both manual coding systems like the GOMS variations and user simulations like those based on ACT-R/PM and EPIC require detailed pseudo-code descriptions of the user workflow with the application interface. Any change to the interface then requires extensive changes to the pseudo-code, a major problem because of the trial-and-error nature of interface design. Updating the models themselves is even more complicated. Even an expert in CPM-GOMS, for example, can't necessarily adapt it to take into account results from new cognitive research.

Our proposal makes automatic interface evaluation easier to use in several ways. First of all, we propose to divide the input to the system into three separate parts, functionality, user traces and interface. By separating the functionality from the interface, even radical interface changes will require updating only that part of the input. The user traces are also defined over the functionality so that they too translate across different interfaces. Second, the parallel modular architecture allows for a lower "entry cost" for using the tool. The system includes a broad array of evaluation modules some of which are very simple and some more complex. The simpler modules use only a subset of the input that a system like GOMS or ACT-R would require. This means that while more input will still lead to better output, interface designers can get minimal evaluations with only minimal information. For example, a visual search module may not require any functionality or user traces in order to determine whether all interface elements are distinct enough to be easy to find. Finally, a parallel modular architecture is much easier to augment with relevant cognitive and design evaluations.

Background / Related Work

Each person should add the background related to their specific aims.

- Steven Ellis - Cognitive models of HCI, including GOMS variations and ACT-R

- EJ - Design Guidelines

- Jon - Perception and Action

- Andrew - Multiple task environments

- Gideon - Cognition and dual systems

- Ian - Interface design process

- Trevor - User trace collection methods (especially any eye-tracking, EEG, ... you want to suggest using)

Cognitive Models

I plan to port over most of the background on cognitive models of HCI from the old proposal

Additions will comprise of:

- CPM-GOMS as a bridge from GOMS architecture to the promising procedural optimization of the Model Human Processor

- Context of CPM development, discuss its relation to original GOMS and KLM

- Establish the tasks which were relevant for optimization when CPM was developed and note that its obsolescence may have been unavoidable

- Focus on CPM as the first step in transitioning from descriptive data, provided by mounting efforts in the cognitive sciences realm to discover the nature of task processing and accomplishment, to prescriptive algorithms which can predict an interface’s efficiency and suggest improvements

- CPM’s purpose as an abstraction of cognitive processing – a symbolic representation not designed for accuracy but precision

- CPM’s successful trials, e.g. Ernestine

- Implications of this project include CPM’s ability to accurately estimate processing at a psychomotor level

- Project does suggest limitations, however, when one attempts to examine more complex tasks which involve deeper and more numerous cognitive processes

- Context of CPM development, discuss its relation to original GOMS and KLM

- ACT-R as an example of a progressive cognitive modeling tool

- A tool clearly built by and for cognitive scientists, and as a result presents a much more accurate view of human processing – helpful for our research

- Built-in automation, which now seems to be a standard feature of cognitive modeling tools

- Still an abstraction of cognitive processing, but makes adaptation to cutting-edge cognitive research findings an integral aspect of its modular structure

- Expand on its focus on multi-tasking, taking what was a huge advance between GOMS and its CPM variation and bringing the simulation several steps closer to approximating the nature of cognition in regards to HCI

- Far more accessible both for researchers and the lay user/designer in its portability to LISP, pre-construction of modules representing cognitive capacities and underlying algorithms modeling paths of cognitive processing

Design guidelines (in progress…)

A multitude of rule sets exist for the design of not only interface, but architecture, city planning, and software development. They can range in scale from one primary rule to as many Christopher Alexander's 253 rules for urban environments,[1] which he introduced with the concept design patterns in the 1970s. Study has likewise been conducted on the use of these rules:[2] guidelines are often only partially understood, indistinct to the developer, and "fraught" with potential usability problems given a real-world situation.

Application to AUE

And yet, the vast majority of guideline sets, including the most popular rulesets, have been arrived at heuristically. The most successful, such as Raskin's and Schneiderman's, have been forged from years of observation instead of empirical study and experimentation. The problem is similar to the problem of circular logic faced by automated usability evaluations: an automated system is limited in the suggestions it can offer to a set of preprogrammed guidelines which have often not been subjected to rigorous experimentation.[3] In the vast majority of existing studies, emphasis has traditionally been placed on either the development of guidelines or the application of existing guidelines to automated evaluation. A mutually-reinforcing development of both simultaneously has not been attempted.

Overlap between rulesets is inevitable and unavoidable. For our purposes of evaluating existing rulesets efficiently, without extracting and analyzing each rule individually, it may be desirable to identify the the overarching principles or philosophy (max. 2 or 3) for a given ruleset and determining their quantitative relevance to problems of cognition.

Popular and seminal examples

Schneiderman's Eight Golden Rules date to 1987 and are arguably the most-cited. They are heuristic, but can be somewhat classified by cognitive objective: at least two rules apply primarily to repeated use, versus discoverability. Up to five of Schneiderman's rules emphasize predictability in the outcomes of operations and increased feedback and control in the agency of the user. His final rule, paradoxically, removes control from the user by suggesting a reduced short-term memory load, which we can arguably classify as simplicity.

Raskin's Design Rules are classified into five principles by the author, augmented by definitions and supporting rules. While one principle is primarily aesthetic (a design problem arguably out of the bounds of this proposal) and one is a basic endorsement of testing, the remaining three begin to reflect philosophies similar to Schneiderman's: reliability or predictability, simplicity or efficiency (which we can construe as two sides of the same coin), and finally he introduces a concept of uninterruptibility.

Maeda's Laws of Simplicity are fewer, and ostensibly emphasize simplicity exclusively, although elements of use as related by Schneiderman's rules and efficiency as defined by Raskin may be facets of this simplicity. Google's corporate mission statement presents Ten Principles, only half of which can be considered true interface guidelines. Efficiency and simplicity are cited explicitly, aesthetics are once again noted as crucial, and working within a user's trust is another application of predictability.

Elements and goals of a guideline set

Myriad rulesets exist, but variation becomes scarce—it indeed seems possible to parse these common rulesets into overarching principles that can be converted to or associated with quantifiable cognitive properties. For example, it is likely simplicity has an analogue in the short-term memory retention or visual retention of the user, vis a vis the rule of Seven, Plus or Minus Two. Predictability likewise may have an analogue in Activity Theory, in regards to a user's perceptual expectations for a given action; uninterruptibility has implications in cognitive task-switching;[4] and so forth.

Within the scope of this proposal, we aim to reduce and refine these philosophies found in seminal rulesets and identify their logical cognitive analogues. By assigning a quantifiable taxonomy to these principles, we will be able to rank and weight them with regard to their real-world applicability, developing a set of "meta-guidelines" and rules for applying them to a given interface in an automated manner. Combined with cognitive models and multi-modal HCI analysis, we seek to develop, in parallel with these guidelines, the interface evaluation system responsible for their application.

Specific Aims and Contributions (to be separated later)

Specific Aims

- Incorporate interaction history mechanisms into a set of existing applications.

- Perform user-study evaluation of history-collection techniques.

- Distill a set of cognitive principles/models, and evaluate empirically?

- Build/buy sensing system to include pupil-tracking, muscle-activity monitoring, auditory recognition.

- Design techniques for manual/semi-automated/automated construction of <insert favorite cognitive model here> from interaction histories and sensing data.

- Design system for posterior analysis of interaction history w.r.t. <insert favorite cognitive model here>, evaluating critical path <or equivalent> trajectories.

- Design cognition-based techniques for detecting bottlenecks in critical paths, and offering optimized alternatives.

- Perform quantitative user-study evaluations, collect qualitative feedback from expert interface designers.

Contributions

- Design-space analysis and quantitative evaluation of cognition-based techniques for assessing user interfaces.

- Design and quantitative evaluation of techniques for suggesting optimized interface-design changes.

- An extensible, multimodal software architecture for capturing user traces integrated with pupil-tracking data, auditory recognition, and muscle-activity monitoring.

- (there may be more here, like testing different cognitive models, generating a markup language to represent interfaces, maybe even a unique metric space for interface usability)

--

See the flowchart for a visual overview of our aims.

In order to use this framework, a designer will have to provide:

- Functional specification - what are the possible interactions between the user and the application. This can be thought of as method signatures, with a name (e.g., setVolume), direction (to user or from user) and a list of value types (boolean, number, text, video, ...) for each interaction.

- GUI specification - a mapping of interactions to interface elements (e.g., setVolume is mapped to the grey knob in the bottom left corner with clockwise turning increasing the input number).

- Functional user traces - sequences of representative ways in which the application is used. Instead of writing them, the designer could have users use the application with a trial interface and then use our methods to generalize the user traces beyond the specific interface (The second method is depicted in the diagram). As a form of pre-processing, the system also generates an interaction transition matrix which lists the probability of each type of interaction given the previous interaction.

- Utility function - this is a weighting of various performance metrics (time, cognitive load, fatigue, etc.), where the weighting expresses the importance of a particular dimension to the user. For example, a user at NASA probably cares more about interface accuracy than speed. By passing this information to our committee of experts, we can create interfaces that are tuned to maximize the utility of a particular user type.

Each of the modules can use all of this information or a subset of it. Our approach stresses flexibility and the ability to give more meaningful feedback the more information is provided. After processing the information sent by the system of experts, the aggregator will output:

- An evaluation of the interface. Evaluations are expressed both in terms of the utility function components (i.e. time, fatigue, cognitive load, etc.), and in terms of the overall utility for this interface (as defined by the utility function). These evaluations are given in the form of an efficiency curve, where the utility received on each dimension can change as the user becomes more accustomed to the interface.

- Suggested improvements for the GUI are also output. These suggestions are meant to optimize the utility function that was input to the system. If a user values accuracy over time, interface suggestions will be made accordingly.

Collecting User Traces

- Owner: Trevor O'Brien

Given an interface, our first step is to run users on the interface and log these user interactions. We want to log actions at a sufficiently low level so that a GOMS model can be generated from the data. When possible, we'd also like to log data using additional sensing technologies, such as pupil-tracking, muscle-activity monitoring and auditory recognition; this information will help to analyze the explicit contributions of perception, cognition and motor skills with respect to user performance.

Generalizing User Traces

- Owner: Trevor O'Brien

The user traces that are collected are tied to a specific interface. In order to use them with different interfaces to the same application, they should be generalized to be based only on the functional description of the application and the user's goal hierarchy. This would abstract away from actions like accessing a menu.

In addition to specific user traces, many modules could use a transition probability matrix based on interaction predictions.

Parallel Framework for Evaluation Modules

- Owner: Adam Darlow, Eric Sodomka

This section will describe in more detail the inputs, outputs and architecture that were presented in the introduction.

Evaluation and Recommendation via Modules

- Owner: E J Kalafarski

This section describes the aggregator, which takes the output of multiple independent modules and aggregates the results to provide (1) an evaluation and (2) recommendations for the user interface. We should explain how the aggregator weights the output of different modules (this could be based on historical performance of each module, or perhaps based on E.J.'s cognitive/HCI guidelines).

Sample Modules

CPM-GOMS

- Owners: Steven Ellis

This module will provide interface evaluations and suggestions based on a CPM-GOMS model of cognition for the given interface. It will provide a quantitative, predictive, cognition-based parameterization of usability. From empirically collected data, user trajectories through the model (critical paths) will be examined, highlighting bottlenecks within the interface, and offering suggested alterations to the interface to induce more optimal user trajectories.

I’m hoping to have some input on this section, because it seems to be the crux of the “black box” into which we take the inputs of interface description, user traces, etc. and get our outputs (time, recommendations, etc.). I know at least a few people have pretty strong thoughts on the matter and we ought to discuss the final structure.

That said – my proposal for the module:

- In my opinion the concept of the Model Human Processor (at least as applied in CPM) is outdated – it’s too economic/overly parsimonious in its conception of human activity. I think we need to create a structure which accounts for more realistic conditions of HCI including multitasking, aspects of distributed cognition (and other relevant uses of tools – as far as I can tell CPM doesn’t take into account any sort of productivity aids), executive control processes of attention, etc. ACT-R appears to take steps towards this but we would probably need to look at their algorithms to know for sure.

- Critical paths will continue to play an important role – we should in fact emphasize that part of this tool’s purpose will be a description not only of ways in which the interface should be modified to best fit a critical path, but also ways in which the user’s ought to be instructed in their use of the path. This feedback mechanism could be bidirectional – if the model’s predictions of the user’s goals are incorrect, the critical path determined will also be incorrect and the interface inherently suboptimal. The user could be prompted with a tooltip explaining in brief why and how the interface has changed, along with options to revert, select other configurations (euphemized by goals), and to view a short video detailing how to properly use the interface.

- Call me crazy but, if we assume designers will be willing to code a model of their interfaces into our ACT-R-esque language, could we allow that model to be fairly transparent to the user, who could use a gui to input their goals to find an analogue in the program which would subsequently rearrange its interface to fit the user’s needs? Even if not useful to the users, such dynamic modeling could really help designers (IMO)

- I think the model should do its best to accept models written for ACT-R and whatever other cognitive models there are out there – gives us the best chance of early adoption

- I would particularly appreciate input on the number/complexity/type of inputs we’ll be using, as well as the same qualities for the output.

HCI Guidelines

- Owner: E J Kalafarski

This section could include an example or two of established design guidelines that could easily be implemented as modules.

Fitts's Law

- Owner: Jon Ericson

This module provides an estimate of the required time to complete various tasks that have been decomposed into formalized sequences of interactions with interface elements, and will provide evaluations and recommendations for optimizing the time required to complete those tasks using the interface.

Inputs

1. A formal description of the interface and its elements (e.g. buttons).

2. A formal description of a particular task and the possible paths through a subset of interface elements that permit the user to accomplish that task.

3. The physical distances between interface elements along those paths.

4. The width of those elements along the most likely axes of motion.

5. Device (e.g. mouse) characteristics including start/stop time and the inherent speed limitations of the device.

Output

The module will then use the Shannon formulation of Fitt's Law to compute the average time needed to complete the task along those paths.

Affordances

- Owner: Jon Ericson

This simple module will provide interface evaluations and recommendations based on a measure of the extent to which the user perceives the relevant affordances of the interface when performing a number of specified tasks.

Inputs

Formalized descriptions of...

1. Interface elements

2. Their associated actions

3. The functions of those actions

4. A particular task

5. User traces for that task.

Inputs (1-4) are then used to generate a "user-independent" space of possible functions that the interface is capable of performing with respect to a given task -- what the interface "affords" the user. From this set of possible interactions, our model will then determine the subset of optimal paths for performing a particular task. The user trace (5) is then used to determine what functions actually were performed in the course of a given task of interest and this information is then compared to the optimal path data to determine the extent to which affordances of the interface are present but not perceived.

Output

The output of this module is a simple ratio of (affordances perceived) / [(relevant affordances present) * (time to complete task)] which provides a quantitative measure of the extent to which the interface is "natural" to use for a particular task.

Workflow, Multi-tasking and Interruptions

- Owner: Andrew Bragdon

There are, at least, two levels at which users work (Gonzales, et al., 2004). Users accomplish individual low-level tasks which are part of larger working spheres; for example, an office worker might send several emails, create several Post-It (TM) note reminders, and then edit a word document, each of these smaller tasks being part of a single larger working sphere of "adding a new section to the website." Thus, it is important to understand this larger workflow context - which often involves extensive levels of multi-tasking, as well as switching between a variety of computing devices and traditional tools, such as notebooks. In this study it was found that the information workers surveyed typically switch individual tasks every 2 minutes and have many simultaneous working spheres which they switch between, on average every 12 minutes. This frenzied pace of switching tasks and switching working spheres suggests that users will not be using a single application or device for a long period of time, and that affordances to support this characteristic pattern of information work are important.

The purpose of this module is to integrate existing work on multi-tasking, interruption and higher-level workflow into a framework which can predict user recovery times from interruptions. Specifically, the goals of this framework will be to:

- Understand the role of the larger workflow context in user interfaces

- Understand the impact of interruptions on user workflow

- Understand how to design software which fits into the larger working spheres in which information work takes place

It is important to point out that because workflow and multi-tasking rely heavily on higher-level brain functioning, it is unrealistic within the scope of this grant to propose a system which can predict user performance given a description of a set of arbitrary software programs. Therefore, we believe this module will function much more in a qualitative role to provide context to the rest of the model. Specifically, our findings related to interruption and multi-tasking will advance the basic research question of "how do you users react to interruptions when using working sets of varying sizes?". This core HCI contribution will help to inform the rest of the outputs of the model in a qualitative manner.

Inputs

N/A

Outputs

N/A

Working Memory Load

- Owner: Gideon Goldin

This module measures how much information the user needs to retain in memory while interacting with the interface and makes suggestions for improvements.

Automaticity of Interaction

- Owner: Gideon Goldin

Measures how easily the interaction with the interface becomes automatic with experience and makes suggestions for improvements.

Integration into the Design Process

- Owner: Ian Spector

This section outlines the process of designing an HCI interface and at what stages our proposal fits in and how.

Preliminary Results

Workflow, Multi-tasking, and Interruption

I. Goals

The goals of the preliminary work are to gain qualitative insight into how information workers practice metawork, and to determine whether people might be better-supported with software which facillitates metawork and interruptions. Thus, the preliminary work should investigate, and demonstrate, the need and impact of the core goals of the project.

II. Methodology

Seven information workers, ages 20-38 (5 male, 2 female), were interviewed to determine which methods they use to "stay organized". An initial list of metawork strategies was established from two pilot interviews, and then a final list was compiled. Participants then responded to a series of 17 questions designed to gain insight into their metawork strategies and process. In addition, verbal interviews were conducted to get additional open-ended feedback.

III. Final Results

A histogram of methods people use to "stay organized" in terms of tracking things they need to do (TODOs), appointments and meetings, etc. is shown in the figure below.

In addition to these methods, participants also used a number of other methods, including:

- iCal

- Notes written in xterms

- "Inbox zero" method of email organization

- iGoogle Notepad (for tasks)

- Tag emails as "TODO", "Important", etc.

- Things (Organizer Software)

- Physical items placed to "remind me of things"

- Sometimes arranging windows on desk

- Keeping browser tabs open

- Bookmarking web pages

- Keep programs/files open scrolled to certain locations sometimes with things selected

In addition, three participants said that when interrupted they "rarely" or "very rarely" were able to resume the task they were working on prior to the interruption. Three of the participants said that they would not actively recommend their metawork strategies for other people, and two said that staying organized was "difficult".

Four participants were neutral to the idea of new tools to help them stay organized and three said that they would like to have such a tool/tools.

IV. Discussion

These results qunatiatively support our hypothesis that there is no clearly dominant set of metawork strategies employed by information workers. This highly fragemented landscape is surprising, even though most information workers work in a similar environment - at a desk, on the phone, in meetings - and with the same types of tools - computers, pens, paper, etc. We believe that this suggests that there are complex tradeoffs between these methods and that no single method is sufficient. We therefore believe that users will be better supported with a new set of software-based metawork tools.

[Criticisms]

- Owner: Andrew Bragdon

Any criticisms or questions we have regarding the proposal can go here.

- ↑ http://hci.rwth-aachen.de/materials/publications/borchers2000a.pdf

- ↑ http://stl.cs.queensu.ca/~graham/cisc836/lectures/readings/tetzlaff-guidelines.pdf

- ↑ http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2000/CSD-00-1105.pdf

- ↑ http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=985692.985715&coll=Portal&dl=ACM&CFID=21136843&CFTOKEN=23841774